- Local News

- Friday-2021-07-02 | 12:10 pm

A skull preserved almost perfectly for more than 140,000 years in northeastern China represents a new species of ancient people more closely related to us than even Neanderthals — and could fundamentally alter our understanding of human evolution, scientists recently announced.

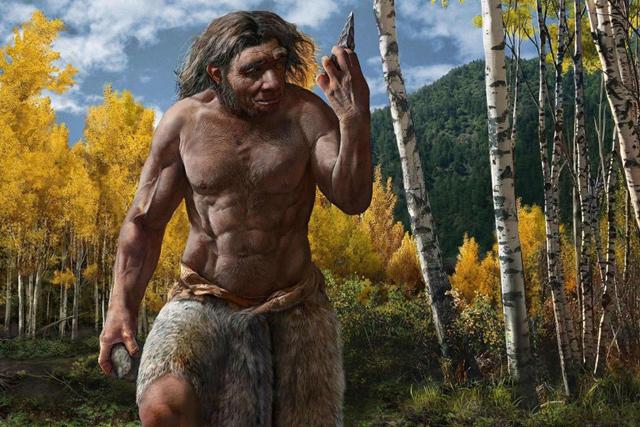

It belonged to a large-brained male in his 50s with deep set eyes and thick brow ridges. Though his face was wide, it had flat, low cheekbones that made him resemble modern people more closely than other extinct members of the human family tree.

The research team has linked the specimen to other Chinese fossil findings and is calling the species Homo longi or "Dragon Man”, a reference to the region where it was discovered.

The Harbin cranium was first found in 1933 in the city of the same name but was reportedly hidden in a well for 85 years to protect it from the Japanese army.

It was later dug up and handed to Ji Qiang, a professor at Hebei GEO University, in 2018.

"On our analyses, the Harbin group is more closely linked to H. sapiens than the Neanderthals are — that is, Harbin shared a more recent common ancestor with us than the Neanderthals did,” co-author Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum, London told AFP.

This, he said, would make Dragon Man our "sister species” and a closer ancestor of modern man than the Neanderthals.

The findings were published in three papers in the journal The Innovation.

The skull dates back at least 146,000 years, placing it in the Middle Pleistocene.

"While it shows typical archaic human features, the Harbin cranium presents a mosaic combination of primitive and derived characters setting itself apart from all the other previously named Homo species,” said Ji, who led the research.

The name is derived from Long Jiang, which literally means "Dragon River”.

Dragon Man probably lived in a forested floodplain environment as part of a small community.

"This population would have been hunter-gatherers, living off the land,” said Stringer. "From the winter temperatures in Harbin today, it looks like they were coping with even harsher cold than the Neanderthals.”

Given the location where the skull was found as well as the large-sized man it implies, the team believe H. longi may have been well adapted for harsh environments and would have been able to disperse throughout Asia.

Family tree

Researchers first studied the cranium, identifying over 600 traits they fed into a computer model that ran millions of simulations to determine the evolutionary history and relationships between different species.

"These suggest that Harbin and some other fossils from China form a third lineage of later humans alongside the Neanderthals and H. sapiens,” explained Stringer.

The other findings include a fossilised skull from the Chinese province of Dali that is thought to be 200,000 years old and was found in 1978, and a jaw found in Tibet dating to 160,000 years ago.

Stringer explained that his Chinese colleagues had decided upon the name H. longi, which he called a "great name”, but said he would have been equally happy to refer to the species as H. Daliensis, which was previously used for the Dali cranium.

More than 100,000 years ago, several human species coexisted across Eurasia and Africa, including our own, Neanderthals and Denisovans, a recently discovered sister species to Neanderthals. "Dragon man” might now be added to that list.

An alternative explanation is that H. longi and Denisovans are in fact one and the same. Fossils so far attributed to Denisovans include teeth and bones but not a full skull, so scientists are unsure what they looked like.

But Neanderthals and Denisovans were genetically closer to each other than to Sapiens, while the new study suggests H. longi were more anatomically similar to us than Neanderthals.

The lingering uncertainty may therefore require future genetic sequencing to help clear up.