- International News

- Tue-2020-06-09 | 03:43 pm

The ultimate concern for Egypt's President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi, they say, is to secure the long western border with Libya, a chaotic battleground of rival administrations, militias and fighters ever since the 2011 downfall and killing of dictator Muammer Qadhafi.

Haftar — a Qadhafi loyalist turned defector who spent years living in the United States — was already in control of oil-rich eastern Libya when in April last year he launched an offensive on Tripoli, seat of the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA).

The 76-year-old military leader's move was viewed as rash by Cairo, according to Tarek Megerisi, a fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

"Egypt has direct security interests in Libya and having a security partner to work with in eastern Libya is of paramount importance to them, which is why they were so concerned at Haftar's reckless adventurism," he said.

The strongman's 14-month onslaught — despite also being supported by Russia and other outside actors — has unravelled spectacularly in recent weeks, as GNA forces, heavily backed by Turkey, have forced his men to fall back from the outskirts of the capital.

Having lost their last outposts in western Libya, pro-Haftar forces have retreated and were Monday defending their positions in the coastal city of Sirte, a gateway to the oilfields and the east.

Egypt is still "invested in propagating the Haftar project diplomatically, providing him political support, and militarily supporting his war effort”, said Megerisi.

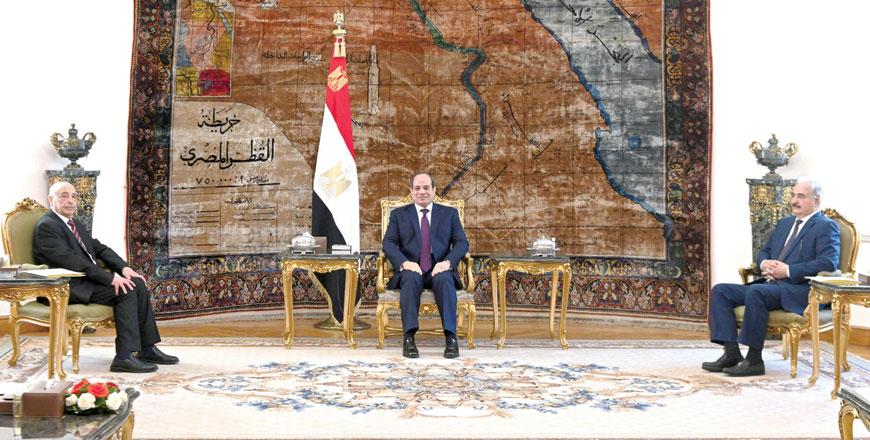

That much could be seen when Haftar appeared alongside Sisi in Cairo at the weekend, where they pushed a time-buying ceasefire — a proposal that found little favour with the GNA, which is keen to maintain the momentum of its counteroffensive.

But at the same time Egypt is "looking for other options and ways to secure their interests as they become less and less certain that he [Haftar] will win”, Megerisi added.

A key facet of this incipient Plan B is Egypt and Russia "working together on political alternatives to Haftar that may be able to save their spheres of influence in eastern Libya”, said Megerisi.

One such alternative figure is Aguila Saleh, the speaker of Libya’s eastern based parliament, who likewise was in Cairo at the weekend, and who has lately been at loggerheads with Haftar.

Egypt heavily invested

Moscow, like Cairo and also Abu Dhabi, has invested in Haftar as a bulwark against the expansion of Ankara’s influence in Libya.

"Egypt has become the main gateway for much of the Emirati and Russian help going into eastern Libya,” explained Jalel Harchaoui of The Hague-based Clingendael Institute.

Harchaoui also pointed to Cairo’s reservations about Haftar’s move on Tripoli — an "initial instinct” that has been "vindicated” by the recent defeats.

But "if, for whatever reason, the conflict worsens a lot from here... Egypt will not remain in a passive posture. It will likely intervene militarily,” he told AFP.

This may take the form of air strikes directly by Egypt, a tactic it used against Daesh in the eastern Libyan city of Derna in 2015.

An Egyptian military expert using the pseudonym Egyptian Defence Review said Cairo remains "a major supplier of arms, training, and logistical support” to Haftar.

It has provided "everything from Cold War-era tanks, fighter jets, helicopters, and assorted ammunition... from their own reserves and in contravention of a UN arms embargo on the country”, the expert said.

This expert pointed to the border town of Sidi Barrani as "one of the main staging areas for arms shipments, Russian mercenary shuttles, and Emirati air power into Libya”.

Limits to escalation

The wider conflict between regional powers playing out in Libya was again made clear in a recent tweet by a key adviser to Abu Dhabi’s powerful Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan.

After Haftar’s men were pushed out of Tripoli’s southern outskirts, the adviser, Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, wrote that "Tripoli has become [the] first Arab capital to fall under Turkish occupation”.

"Count on Egypt and its military playing a decisive role... it will deter [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan and stop his mercenaries’ advances east, west and south.”

But while Egypt will likely invest further in protecting its interests in the east, it has no appetite for direct confrontation with the GNA’s main backer Turkey, analysts say.

The ceasefire proposed by Sisi shows how the "political desire to see a bigger, more uncertain war against Turkey... is just not there in Cairo”, according to Harchaoui.

The Egyptian Defence Review also believes that Ankara, as well as Cairo, has little appetite for direct confrontation.

"Egypt’s interests in Libya and the Mediterranean sea are primarily represented in the security of their western border and economic exclusive zone sovereignty.

"Turkey... will likely respect Egypt’s security and economic interests in order to avoid any form of direct confrontation.”