- Local News

- Sun-2020-09-27 | 03:15 pm

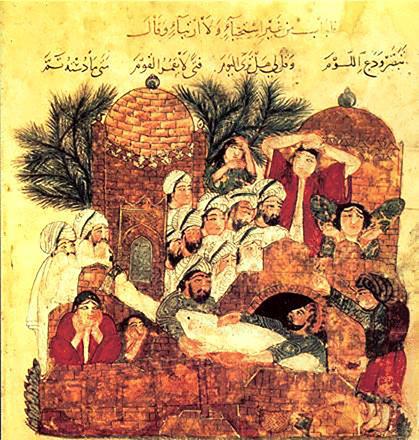

As the novel coronavirus continues its spread across the world, a British-trained archaeologist and historical demographer has recalled the Plague of Amwas that afflicted the eponymous Palestinians village in 639AD and spread towards neighbouring regions.

In January and February 639AD, the plague descended on Amwas (Byzantine Nicopolis), 32km west of Jerusalem, where the Muslim armies were garrisoned, said Caludine Dauphin, who has devoted the last 30 years to the historical demographic study of the populations of Palestine and Jordan in the Byzantine and Early Islamic period in their landscapes, their diet, state of health, environment and epidemics.

"The number of victims is estimated between 25,000 and 30,000 in the army alone," Dauphin told The Jordan Times.

It is possible that the bubonic plague, starting in January, rapidly turned into a pneumonic plague, she added- a winter and particularly infectious phenomenon, "which may be the reason for the extent of the scourge".

By striking down the military commander of Syria Abu Ubayda Bin Al Jarrah, his successor Mu'âdh Bin Jabal, as well as his two wives and his son, the Plague of Amwas "decapitated" the Arab military hierarchy and became the focus of all hadiths (sayings of Prophet Mohammad) concerning plagues in general, the archaeologist continued.

According to Dauphin, the pandemic was preceded by a severe drought and famine and it was the second resurgence of the Justinian Plague of 541-549AD, which remerged in Constantinople in 558AD.

"The plague hit the new occupants of Palestine hard, a population that had not previously been exposed to infectious pathogenic microorganisms and therefore, there was no herd immunity," she said, highlighting that the Amwas Plague affected virtually everyone, regardless of age and had high fatality rates.

Moreover, the importance of the demographic disaster may be measured by the number of young men killed: 73, even 83, sons of a same father, and 40 of another, according to the Iraqi historian Abu Al Hasan Al Madaini (752AD-843AD), directly affected the reproductive power of an entire generation, Dauphin said

"In order to save his armies from death, Caliph Omar Ibn Khattab [634AD-644AD] ordered all units garrisoned in Syria and Palestine to flee from population centres and to pitch their tents in the desert," Dauphin recounted.

The low density of the nomadic population, the lack of contacts and, especially, "the habit of abandoning the sick with basic food supply in the desert”, curbed the spread of the epidemic, according to the scholar.

Nevertheless, the epidemic spread from Amwas across Palestine and Syria to civilian population and continued "to empty” the countryside of its population, the archaeologist noted.

The decline of agriculture, heralded by drought and famine from 516 to 521AD, accelerated after the Amwas Plague, and brought about another famine, Dauphin said.

"Weakened by chronic malnutrition, the population of Syria was predisposed to be hit again by plague in 676AD. The cold wave which unfurled over Syria and Mesopotamia in the winter of 683-684 — the olive trees and vines became stunted, domesticated animals, wild beasts and fowl perished — brought dearth until 685AD, this facilitating the resurgence of plague, " Dauphine narrated.

"A three-month long drought in the winter of 686-687AD caused a bad harvest", the scholar said.

However, it was not the end of the pestilence. In 689AD, in "the Year of Mud", ceaseless rain increased humidity and rats proliferated.

The Plague of the Torrent broke out in April 689AD and according to the scribe, Abu Al Hasan Al Madaini, in three successive days, 70,000, 71,000 and 73,000 persons died in Basra, in southern Mesopotamia, Dauphin said.

"Famine had also raged between 683AD and 686AD in Egypt, across which the plague swept in 685-686AD. Held in pincers between Syria and Egypt, Palestine, like other adjacent countries, was most probably also ‘attacked’, but to a lesser degree,” she said.

The "plague-famine-plague" cycle perpetuated itself in 697AD, 700AD, 716-717AD, 725-726AD and 733-735AD, with a last flare in 750 AD in the Jordan Valley, Dauphin said.

"These resurgences emit a strong historical warning: Economic collapse resulting from an epidemic paves the way to famine and to a return of that epidemic," Dauphin underscored.