- International News

- Mon-2020-12-21 | 03:32 pm

Brussels: Most people think they know what waste is. It's the plastic they rip off their broccoli and toss in the bin. It's the cardboard box their new laptop arrives in, and that laptop itself, once it's no longer useful.

Every year, the world produces roughly 2 billion metric tonnes of garbage. But this is just the trash we can see.

"The

waste we deal with as consumers is a tiny percentage of the overall

waste — only about 2 to 3 per cent of it," said Josh Lepawsky, author of

a book on the global impact of making digital technology.

Hidden

in the difficult-to-trace processes of resource extraction,

manufacturing, transportation and electricity production is the bulk of

the world's waste — generated to make the stuff we buy.

This

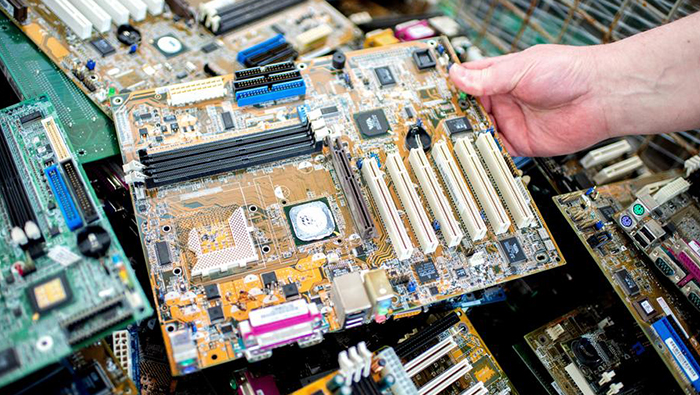

is especially true for electronics, which is the world's fastest growing

trash stream and one of the largest sources of invisible waste.

"Most

of the pollution and waste from electronics happens long before people

have their devices in their hands," said Lepawsky, who is also a

professor of geography at the Memorial University of Newfoundland in St.

John's, Canada.

Producing electronics involves high levels of hazardous chemicals, greenhouse gases and water drainage.

Most

of this is totally invisible to the average consumer and difficult to

quantify. Electronics are comprised of numerous components, most of them

sourced and manufactured in different locations around the world before

being assembled somewhere else entirely.

Mining precious metals

A

typical smartphone, for example, can comprise up to 62 different

metals. Among the myriad tiny components of an Apple iPhone are gold,

silver and palladium. These precious metals — extracted mostly in Asia,

Africa and Australia — need to be mined.

A study by Swedish waste

management and recycling association Avfall Sverige calculated the

invisible waste generated for a typical smartphone and 3-kilogram laptop

to be about 86 and 1,200 kilograms (190 and 2,645 pounds) respectively.

"That [figure] includes stones, gravel, tailings and slag,"

said Anna Carin Gripwall, co-author of the study. "It's also the fuel

and electricity used — but that is a very small amount compared to the

mining waste."

This far outweighs other products surveyed,

including one kilogram of beef and a pair of cotton trousers, which

generate 4 and 25 kilograms respectively.

A dirty enterprise

The

cutting, drilling, blasting, transportation and processing involved in

mining precious metals can release dust containing harmful metals and

chemicals into the air and surrounding water sources.

"After you dig up the ore, you have to separate out the concentrated material," said Fu Zhao, professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University in the US state of Indiana. "They are difficult to break down, so you need to use chemicals and high temperatures." This becomes particularly problematic when done on such a large scale, he added.

Without proper oversight, these toxic components can contaminate groundwater, leach into valleys and streams and damage soil, plants and animals — and threaten the health of human populations.

This doesn't necessarily mean that mining for these precious metals is inherently bad for the environment, said Saleem Ali, professor of energy and environment at the University of Delaware in the US.

"The challenge is just figuring out how to manage it so it doesn't damage the environment," he said. "You have to find a way that these toxic solvents don't enter the groundwater supply, and give people working in these areas protective equipment so they aren't inhaling volatile organics." This can be done, he argues, with more investment.

An

important part of achieving "green mining" is using more renewable

sources of energy in the making of these devices, said Ali.

Most

electronics are now manufactured in China, Hong Kong, the United States

and countries in Southeast Asia. Part of the difficulty of putting

invisible waste into concrete terms is that many modern products,

especially electronics, have long, complicated supply chains.

Although

Apple publishes a list of its top 200 suppliers located in 27 different

countries, the bulk of their supplier's facilities are in places with

no publicly accessible registers tracking the release of toxic

pollutants.

And as for the world's electronic devices we throw away — currently, only 17.4% is formally collected and recycled.

Even if 100 per cent of these electronics were successfully recycled, it would do nothing to recoup the pollution and waste arising in manufacturing, and only make a minor difference to mining waste, said Lepawsky. The lack of e-waste recycling does, however, highlight part of the problem.

"If you look at electronics, they are not designed for reuse or remanufacture," Zhao said.

Apple

has pledged to become 100 per cent carbon neutral by 2030 and has

recently responded to growing concerns about e-waste by deciding not to

sell earphones and chargers with every iPhone, as well as promising to

increase the use of recycled materials in its production.

Yet

Zhao said such rapid technological advancements housed in very complex

and difficult to disassemble device make those goals a challenge.

"Your cell phone might become obsolete in just a couple of years... That makes reuse and remanufacture almost impossible," he said. "The tech companies have to make money... But at the same time, that has consequences for the environment."